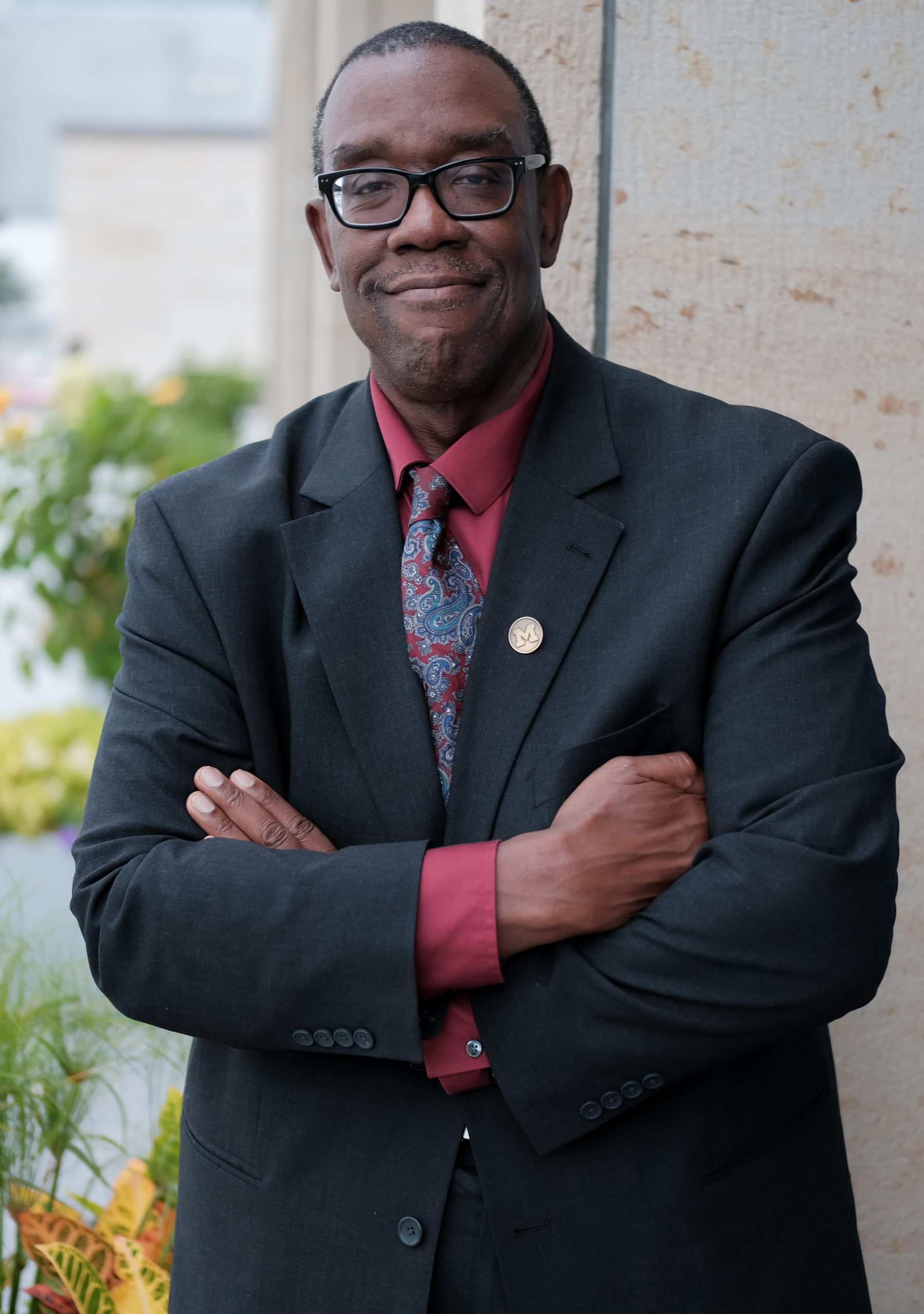

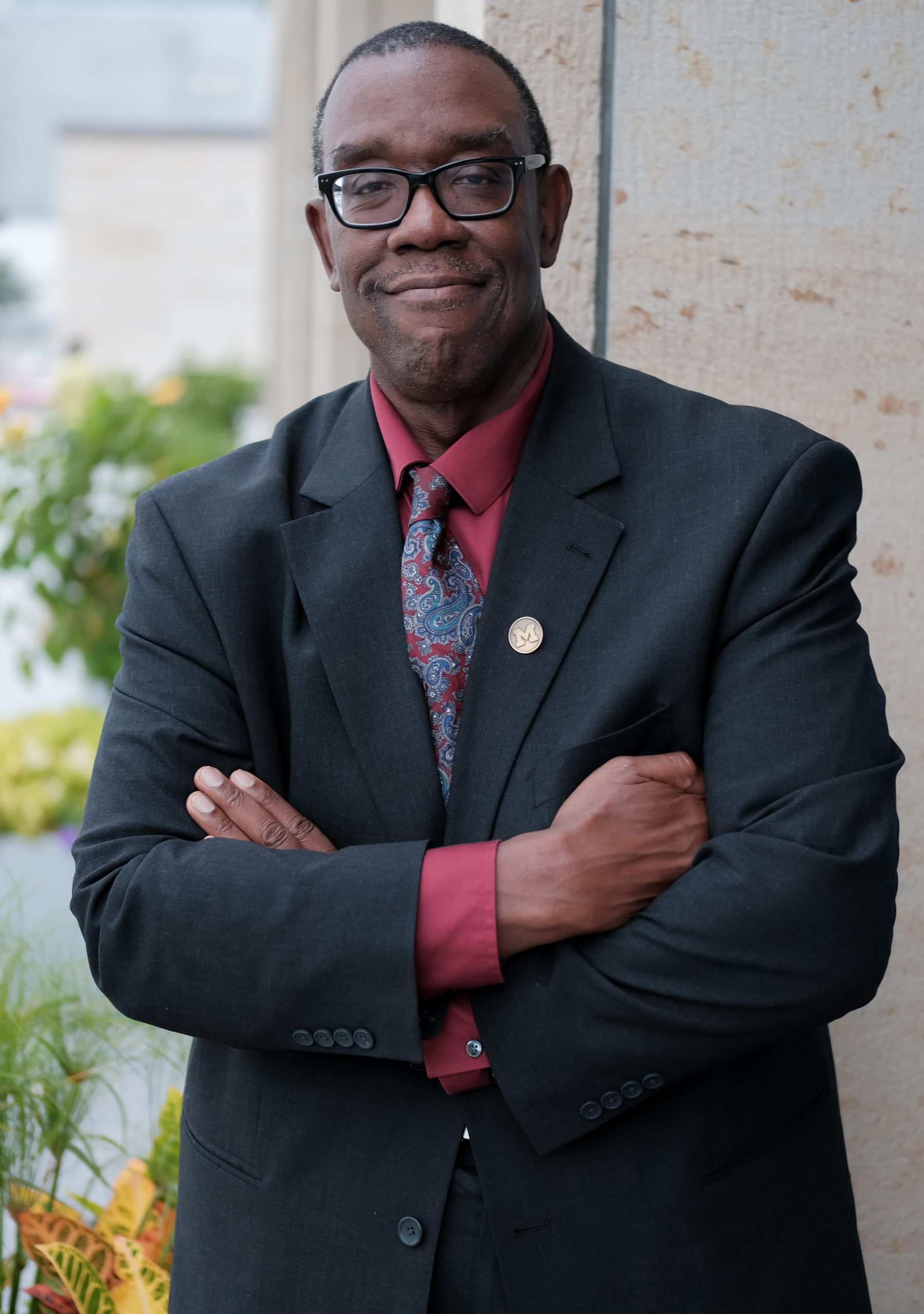

Alumni profile: A conversation with Robert Scott

A Michigan engineer and a corporate leader, Robert Scott is a team builder, a mentor to many, and champion for diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Robert Scott graduated from Michigan with a BSE in computer engineering in 1975. After graduation, he embarked upon a 32-year career at Procter & Gamble, during which he served in numerous leadership roles in strategic planning and analysis, IT management, product distribution, and global learning systems. In addition to his line responsibilities, Mr. Scott served as P&G’s corporate leader for an organizational development program providing facilitated training to build high performing global teams.

Mr. Scott returned to the University of Michigan and founded the Center for Engineering Diversity & Outreach at the College of Engineering. He also participated in the creation of the College’s Diversity, Equity & Inclusion plan.

We recently spoke with Mr. Scott about his journey, his philosophy, and his current activities.

How did you become interested in computers?

I was born and raised in Kalamazoo, Michigan and attended high school in the late 1960s. Computing was just starting to get a foothold and it wasn’t something you saw much in daily life.

Prior to high school, I was keenly interested in the space program. I grew up with rockets taking off and the anticipation leading up to the moon landings, and I used to write to the various NASA installations asking for materials. I would be very excited when I got a packet of what in hindsight was probably the usual publicity stuff. But one of the things I learned was that computers were helping to drive how scientists were thinking about doing space travel, so that got me to thinking about computers.

While I was in high school, one of my teachers provided me with a great opportunity by enabling me to have access to the Board of Education’s computer at night. So I actually wrote my first programs in about 1970. That just reinforced my interest in computers.

I was also very fortunate that my high school counselor, Mrs. Juanita Goodwin, insisted on shepherding my college career because at that time it was very easy to get trapped either towards or away from college. She made up her mind that I was going to go to college and took it upon herself to make sure that I took college prep courses, even going so far as to actually tear up my elective sheets that had the “wrong” courses on them and rewriting them with college prep courses.

Mrs. Goodwin basically said, “Okay, you’re interested in computers. You need to go to college. Let’s be clear right now – you’re not going to be a computer operator; you need to be a computer engineer or a computer scientist. Let’s talk about schools where you can do that.” And eventually Michigan emerged as the leading choice.

I applied and got accepted to Michigan knowing that I wanted to be in computers. I didn’t really know what that meant at first, but I knew that’s what I wanted to do.

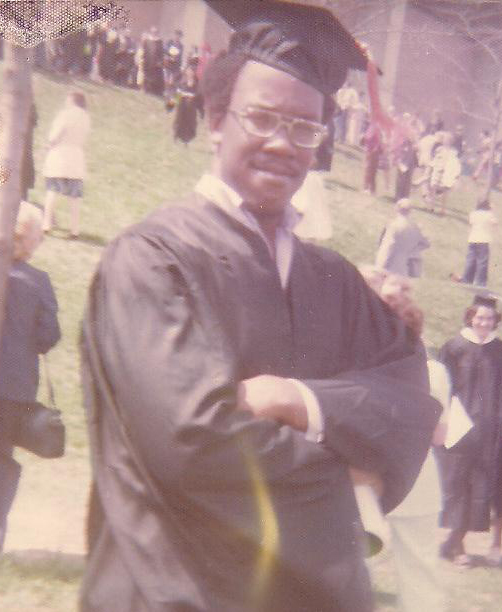

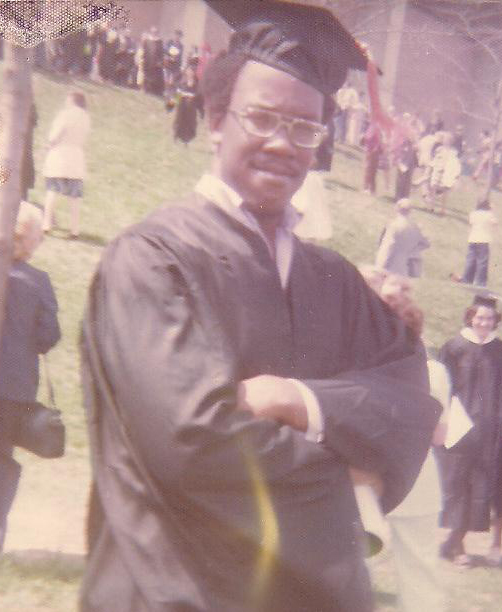

When I arrived at Michigan in 1971, computers were these things in their own rooms that basically did arithmetic. So I actually started my engineering classes on slide rules. During my time in school, I moved from slide rules to programmable calculators to computers, and by the time I graduated with my computer engineering degree, I was working on writing operating system code and doing analog computer programming.

So that’s how it all got started. A lot of it was happenstance. And a lot of it was passion about something that I didn’t fully understand what I was passionate about. And really importantly, a lot of it was mentors looking out for me and steering me in the right direction when I didn’t really know where I was going.

What was it like to be a Black student at Michigan?

During my freshman and sophomore year, I was one of a handful of Black engineering students and I pretty much got ignored in classes. I think the assumption was: he won’t be around long, so there’s no point in paying any attention to him.

My freshman year I stayed in East Quad. I actually had a single room as a freshman, which was pretty unusual. Looking back on it, this was in 1971 and they probably didn’t want to put a Black student with roommates if they could help it.

There were a handful – six or eight – of other Black students, mostly in LS&A, who also lived in East Quad. And so we kind of banded together.

Enlarge

Enlarge

We had a room where we went to study together that was down in the basement of East Quad, and the janitor began referring to it as the “colored room.” And while we felt that was an insult, we also took it as also a badge of honor. So we actually adopted the name and would say, “Let’s meet in the Colored Room tonight to study.” We would go there and help each other to absorb the material in order to get through the math, chemistry, and physics “weeder” courses that made or broke you back in those days.

So there was a lot of isolation, but also some banding together in this group and in later small groups to try to help each other out. And quite honestly, I felt a lot of trepidation from an imposter syndrome standpoint that I was going to get found out, and eventually kicked out.

Every single semester of my career at Michigan, I would call my mother at some point in time during the semester and tell her that “this is the semester that I flunk out.” But every single semester at Michigan I made the dean’s list. That’s the psychological pressure that we were going through.

The atmosphere around me changed as I became a junior because people started to say, “Hey, he’s still here. There must be something going on; let’s try to figure out who this guy is and what’s going on with him.”

But in those days we didn’t have the focus on teams and team projects that we have now. So you might become noticed, but it was all individual contributor, individual focus. The engineering Honor Code was really the rule of law. Everything you did, you did on your own and you adhered to that. And so throughout my college career, it was focused on me getting through this stuff and it was doing it on my own by myself.

You’re known now for your focus on teams and mentorship, and you led in that way at Procter & Gamble. How did that philosophy take shape?

First of all, I was told early on when I got to P&G that I was one of the best technically prepared new hires that they had ever had. So that’s a testimony to Michigan and the power of its educational process.

On the other hand, they basically sat me down and said, “You know that engineering honor code where you neither give nor receive aid? You need to forget that. That’s not how business operates. We want you to get aid and we want you to give aid; that’s the way things get done here.”

So I literally had to unlearn that fundamental credo which had been built into me for the past four years. Everything about work in industry and engineering is a team sport. It’s not an individual sport.

And I had to learn that quickly. Fortunately, I was put on some project teams and in some organizations that kind of reached out to me and embraced me and pulled me into things in a very proactive way, and I got an early opportunity to work on some groundbreaking technical projects. This helped me to join that team sport mentality.

After a few years, I was sent to Chicago as the IT systems engineer/manager for the manufacturing plant there. It was a standalone plant at P&G, so this was a “big fish in a little pond” kind of role for me. That helped me to grow and blossom really quickly in terms of not only my technical skills and responsibilities, but also my interpersonal skills, my relationship skills, and my management skills as well.

When did you realize that you were inclined to be a technical manager as opposed to a nuts and bolts type of engineer?

At P&G, there were career paths for those who wanted to progress on the managerial track and on the technical track. I never really got to decide about which one was right for me.

My position in Chicago was really sort of a hybrid of both, and the mentors and the sponsors that knew and saw me in that role said, “You should be a manager; you have this leadership capability. You can do this.” And so I kind of got guided that way very early in my career. It’s like how I ended up at Michigan; my counsellor said Michigan is the school to go to, so go to Michigan. And I ended up at Michigan.

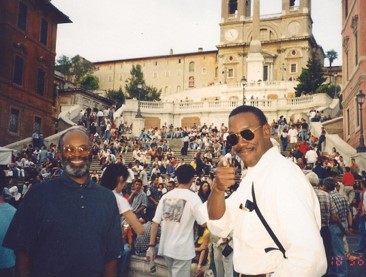

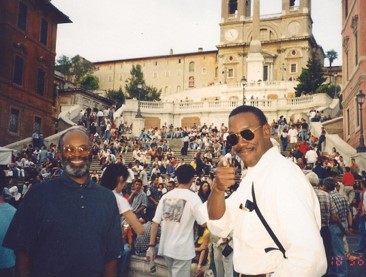

Your career has taken you to some incredible places.

Enlarge

Enlarge

I had a fantastic career at P&G. I was able to work in virtually every function within the company from an IT perspective. The soap business, the food and beverage business, the health and beauty aids business, manufacturing, sales, marketing, distribution, and it all traced back to the two years in Chicago.

I mean, I grew up in Kalamazoo. So to me, Cincinnati, where P&G is headquartered, was a big city. Then I got transferred to Chicago and I learned what a big city really is. But P&G helped to mature me that way.

And following that I gained global responsibilities and ultimately I transferred to Europe for four years. I moved to Belgium in 1997 and was there until 2001, which meant that I was leading the P&G IT organization for Europe, Middle East, and Africa when we went through the big millennium bug issue. That was huge, because computer systems everywhere were expected to break when the calendar flipped to 2000, and I was the guy who had to make sure that didn’t happen.

I thought the millennium bug was the biggest thing ever. Then, Europe decided to move to the Euro, and the conversion to the Euro was actually bigger than the millennium bug issue from a technology standpoint. So I actually got to oversee both of those things while I was in Europe.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Did you ever have to overcome discrimination in the workplace?

Absolutely. There are always things to overcome, including my own biases. We all have biases.

When I first started at P&G, I was in this great organization, but I would always choose for whatever reason to leave my work team and go have lunch with the other handful of Black employees working in the same building. One of my managers eventually came to me and said, “Look, you’re isolating yourself by choosing to step away at lunch; you’ve got to open up your vistas and expand your circle.” That was an eye opener for me.

I’ve faced many instances where my technical credibility was challenged. At times when I was the technical leader present, someone would try to talk to one of my subordinates instead of me. And I would have to pick my battles on how I wanted to respond to that.

P&G, to its credit, enabled employee affinity groups to come together where we could talk about the issues we were facing and how to be successful. I took a number of workshops and classes that helped me develop strategies and skills for how to deal effectively across diversity dimensions and I had to invest in that, including understanding my own biases that I would bring to a situation, or my own survivor syndrome, and how issues like protective hesitation impact you.

I began talking to young people a lot about protective hesitation for women and minorities, which is a hesitancy to put yourself and your ideas out there for fear that they are going to be rejected, or that they’re not good enough. By protecting yourself in this way you’re actually blocking yourself from being perceived as bringing something to the party.

Increasingly, as I moved up the ladder the demands on me as a mentor and sponsor increased, which is a good thing. But it also brings with it a lot of stress and expectations, some of which are very unrealistic: “Robert, you should be able to fix this, you’re in the room; make this right, advocate for me. Get me in this position.” Maybe I can do that, but maybe I can’t. Maybe you’re ready for it, or maybe you aren’t. I can’t do that for you just because you happen to have the same skin color as I do.

So, those tensions are always there around “Am I advocating enough?” and “Am I developing people enough?” What it’s done for me though, is it’s told me that as I continue to move through life, my ultimate responsibility is to do what was done for me, which is to create opportunities and platforms for other people to be successful.

That’s why I chose to come back to Michigan after I retired from P&G. It was very simple: to whom much is given, much is required.

How did the idea for CEDO at Michigan come about?

My original return to Michigan was dual engagements with the College of Engineering and the Business School. The College of Engineering basically said, “Look, you’re a business guy, and we would like to bring a sense of business understanding and perspective to our diversity outreach and development efforts. So come in and just be a council to the folks that are running those programs.”

The Business School, on the other hand, had me running their CIO Roundtable, which I did from 2008–2010. Ultimately, I decided I wanted to focus my energies on the programs at the College in more than an advisory role, and so that’s the direction I went.

After having been engaged with the college for two or three years, it had become apparent that we had an effort focused on diversity and outreach for minority students, another focus on programs for women, and that we were doing these and other similar kinds of things, but in an inefficient and fragmented way. That became the impetus for the creation of the Center for Engineering Diversity & Outreach (CEDO), which is about bringing all of these activities together and strengthening them under a single umbrella.

So I drove the initiative to do that. And as a result, was asked to be the initial Managing Director for CEDO.

You’ve also been involved in the College’s DEI initiative.

That’s right. This began when President Schlissel asked every school and college to develop a five-year DEI strategic plan. Having managed CEDO for five or six years, I was in position to step away from that and to join then Associate Deans Alec Gallimore and Jennifer Linderman on the initial development of the first draft of the DEI plan.

Midway through the drafting of that plan, Alec became the next Dean of Engineering. So Jennifer and I finished writing the first draft of the plan and put it forward to Alec, and then got the college organized with a DEI committee. I then continued to serve as a steward and facilitator for that program for the next three years.

Where are you now with U-M and other pursuits?

I retired from the College in August 2020, but was immediately retained as a temporary employee as a part of CEDO, focused primarily on DEI-related workshops and training. Outside of Engineering, I am also working on the potential for leading a set of unconscious bias workshops for the University Museum System.

In addition to my involvement at Michigan, since 2016 I have served as the Vice President and Dean for the IT Senior Management Forum, an organization that has been in existence for 25 years with a focus on the growth and development of senior IT leaders of color. In this role, I oversee three academies: a middle-level manager academy, a senior executive academy, and an academy for women of color.

I’m also doing a number of in-house workshops for companies including Boeing, Amazon, PepsiCo, and Capital One to grow and develop their leaders of color.

And then other duties as assigned in that space as well. It’s all on this platform of “What can I do to help the next generation of leaders of color get developed and in place so that they can pick up the mantle and carry forward?”

And so I’ve failed retirement from Procter & Gamble, I’m now failing retirement from the University of Michigan, and my wife just looked at me yesterday and said, “Let’s not even talk about failing retirement because you’ll never really retire.” So I’ve started talking about “preferment.” I am in preferment. I do what I prefer, and that’s about lifting people up.

MENU

MENU